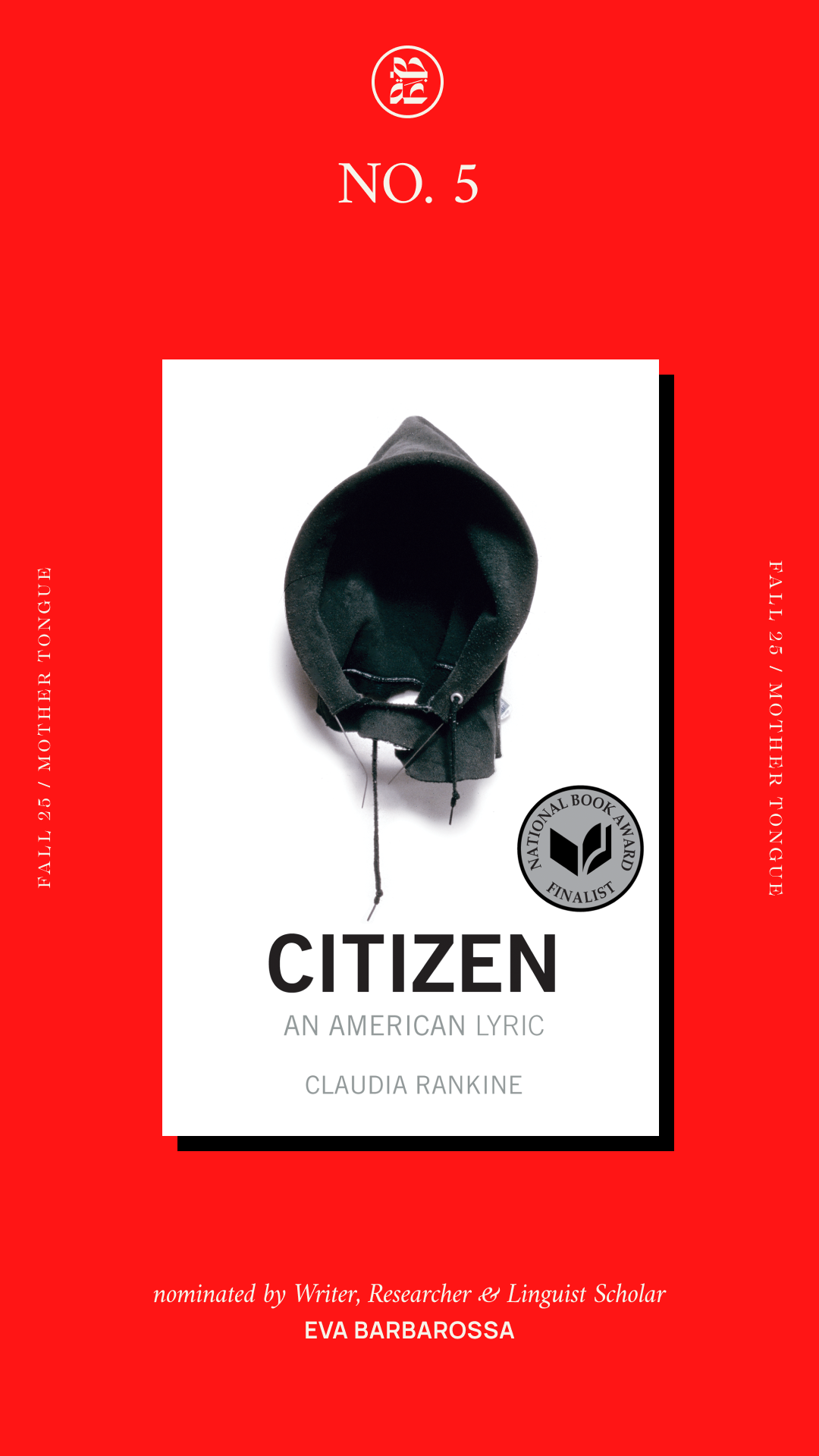

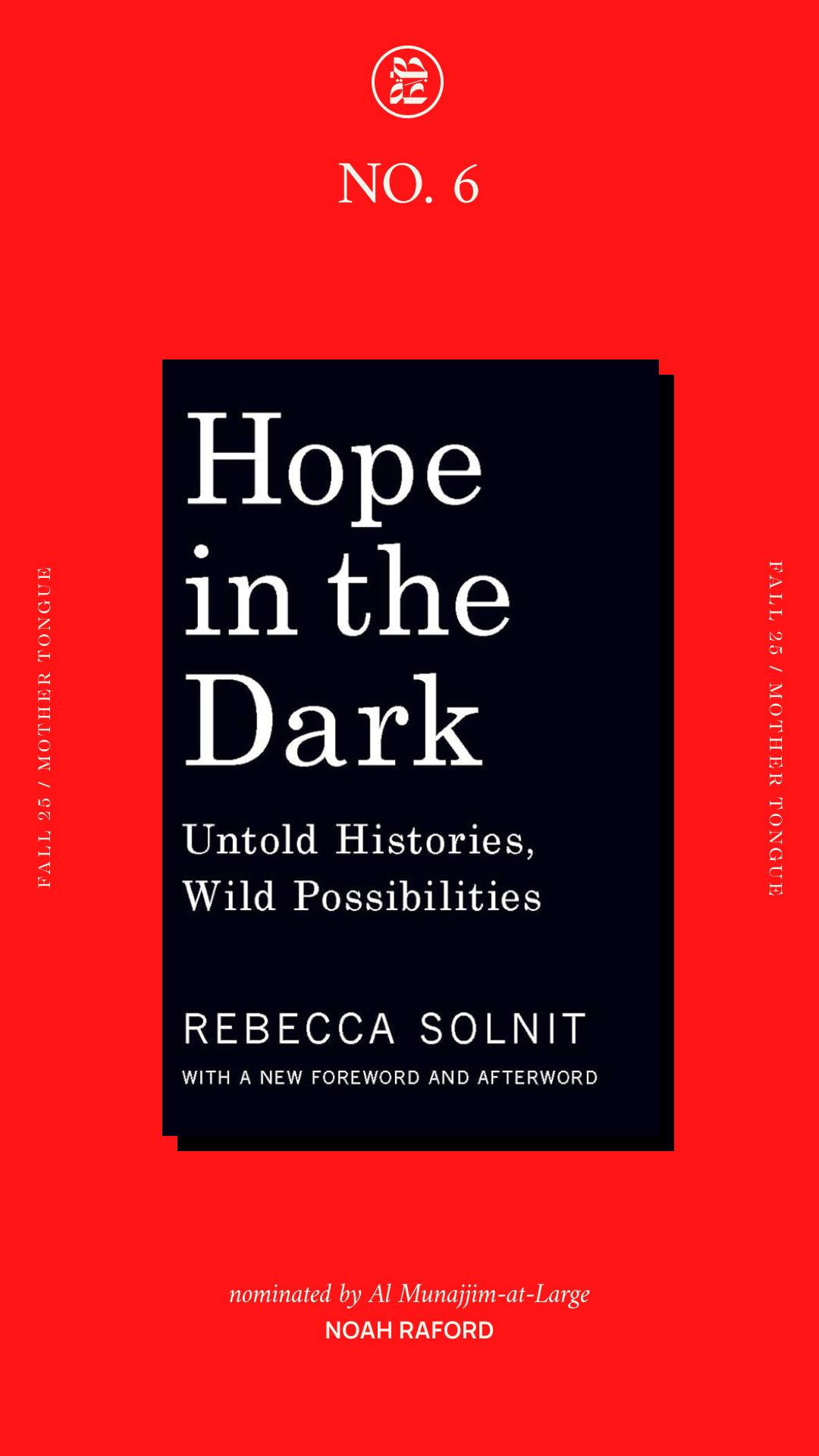

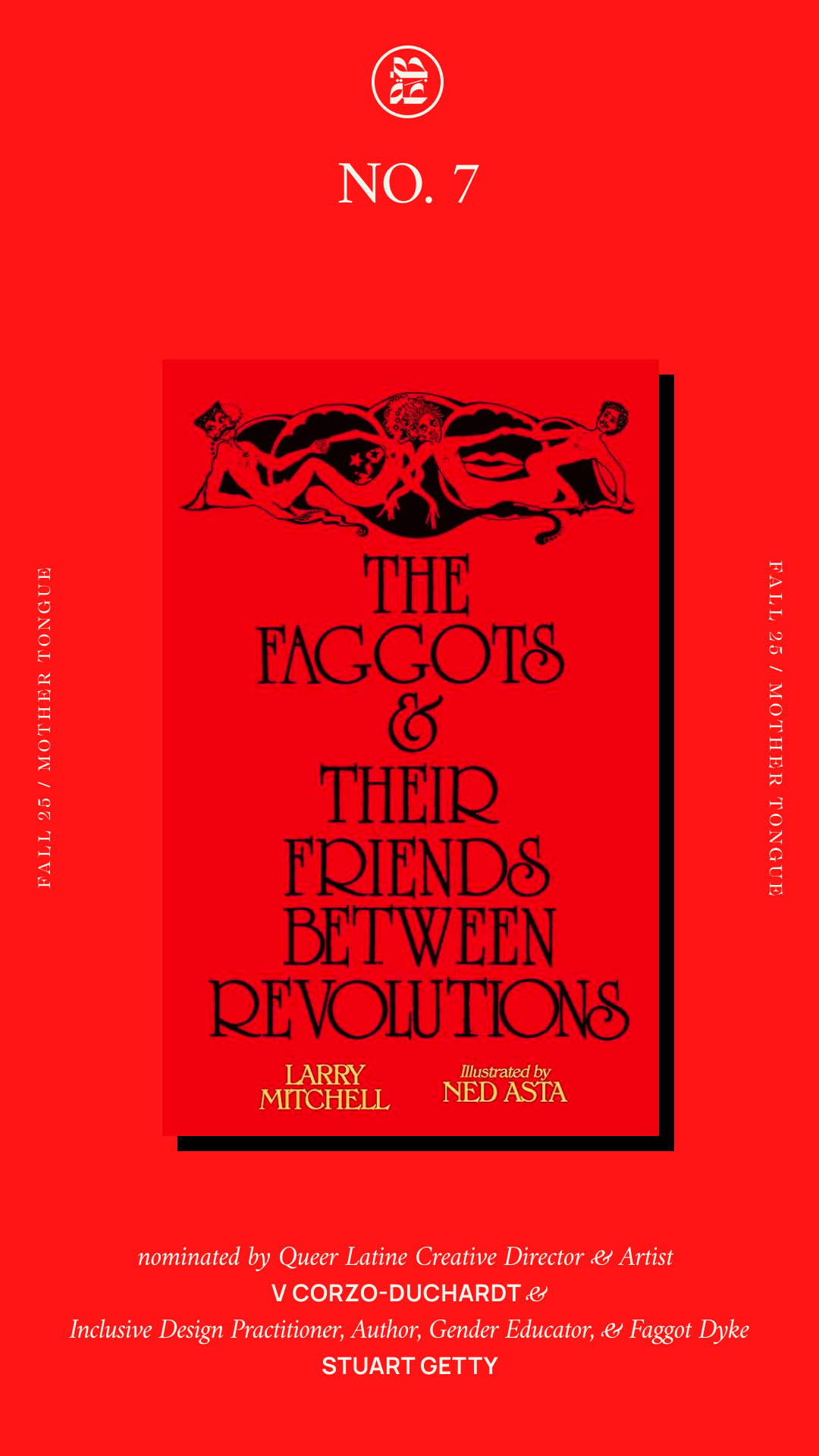

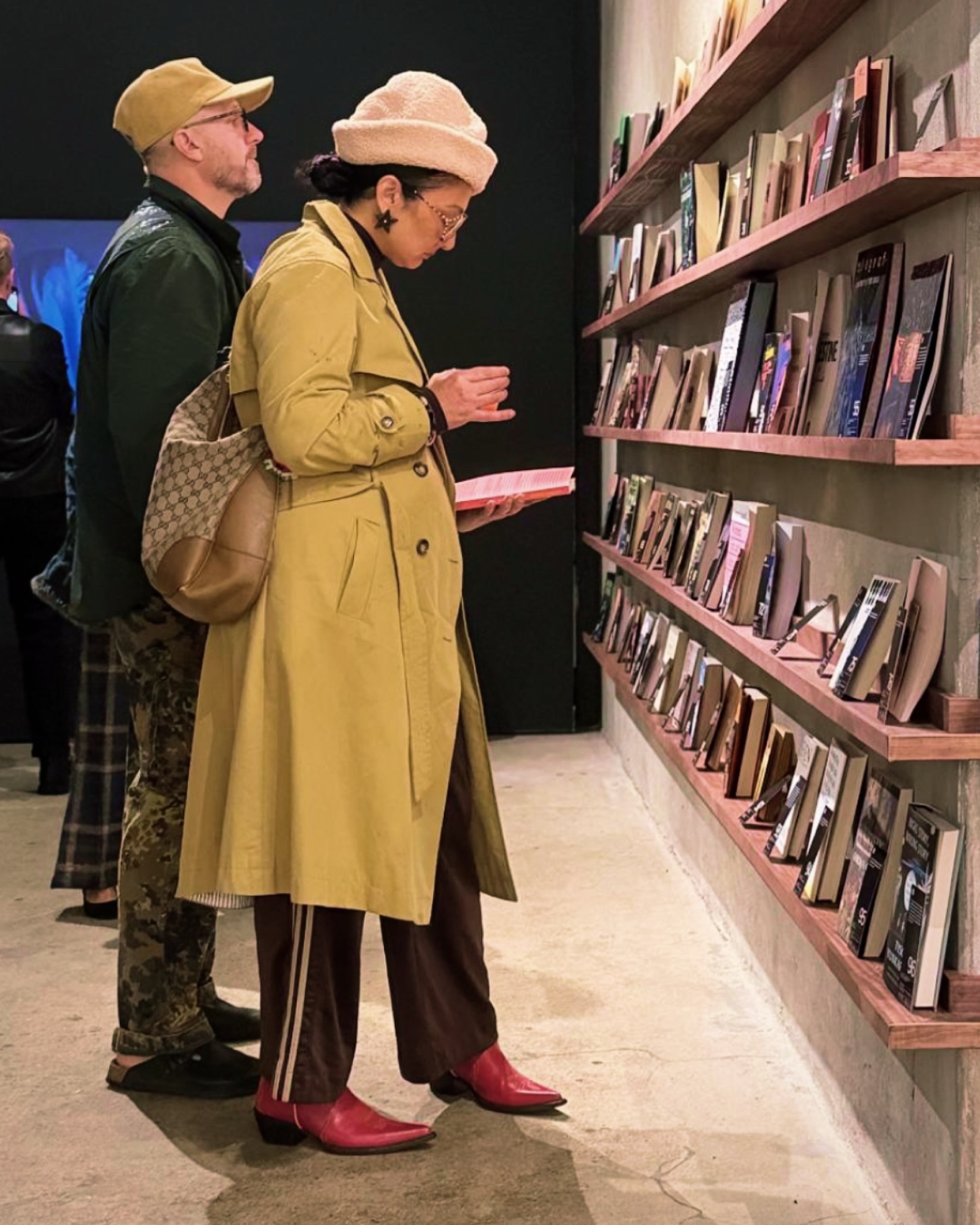

THE MOTHER TONGUE LIBRARY

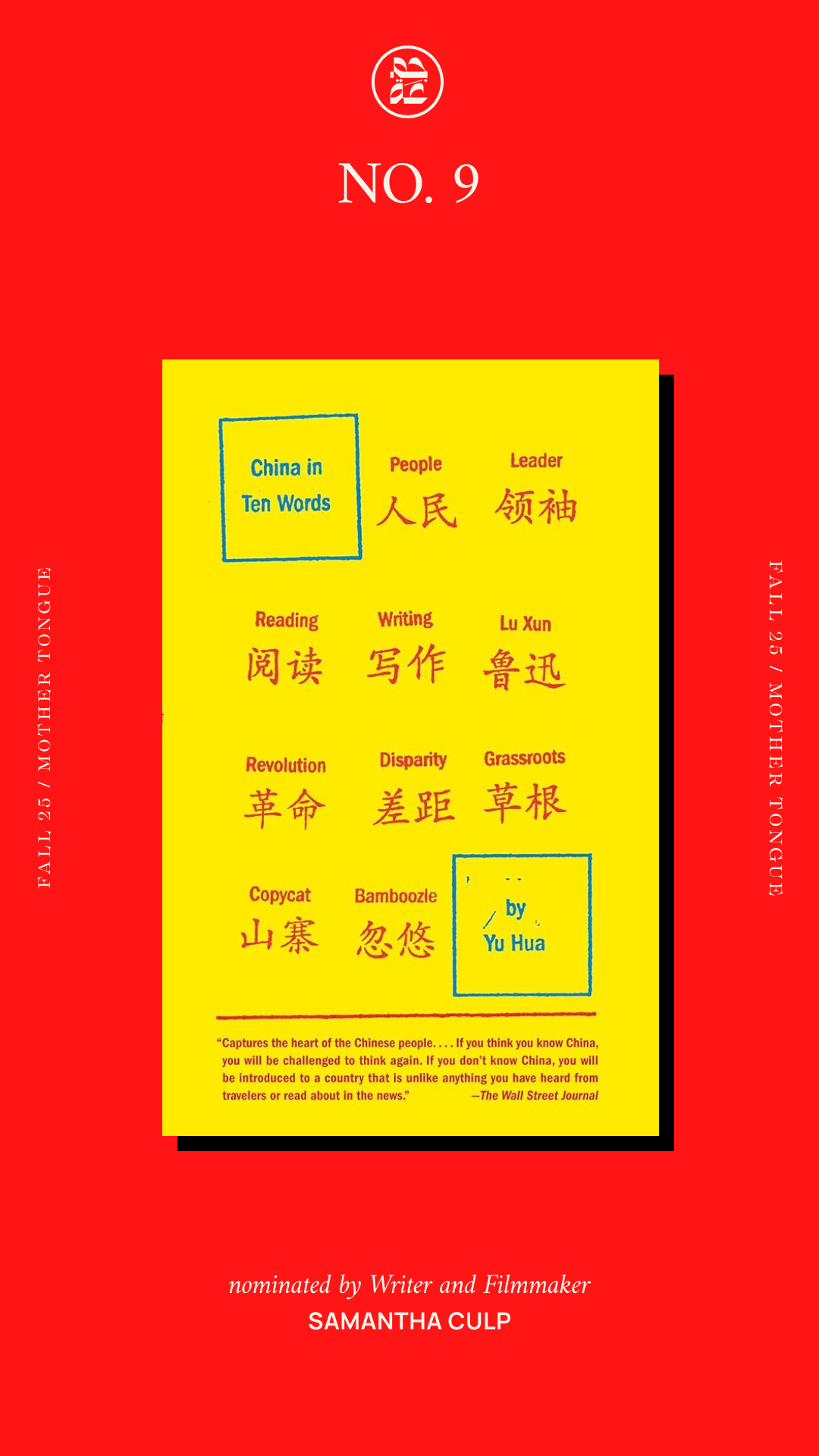

A Living Library of 100 Books, chosen by 100 cultural thinkers and curated by linguist scholar Eva Barbarossa. The library weaves together diverse perspectives on power and language: from the conversations of plants, to the secret lexicon of an extinct female-only language.

The Mother Tongue library is a love letter to the thinkers, writers, and artists who’ve given us the language of courage when we needed it most. Borrow and exchange as you wish during our Fall 25 season.

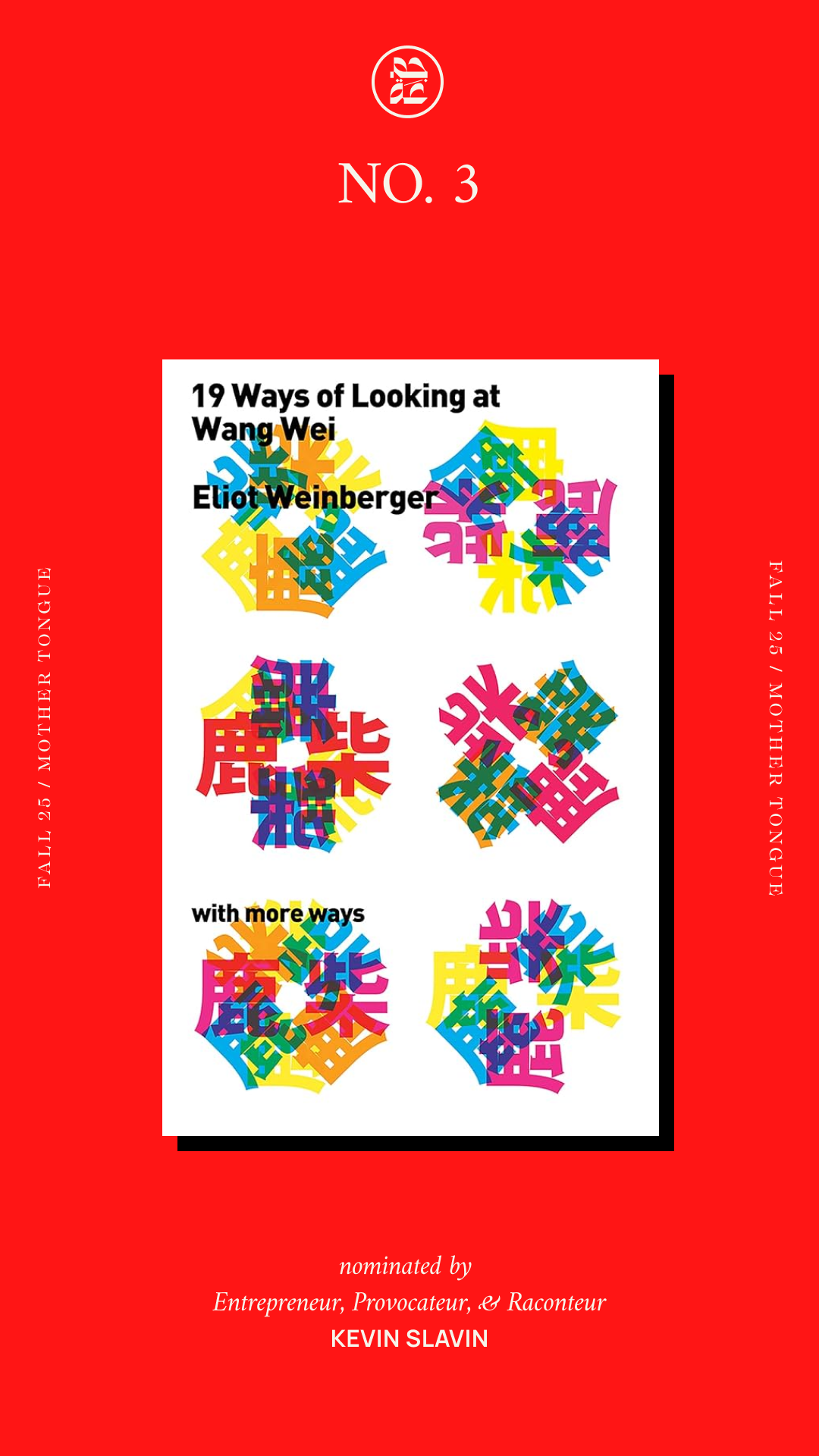

download the books

a library of power

A compilation of all 100 books, along with personal notes from each nominator of why they believe this book belongs in a library exploring power and language.

Explore the library

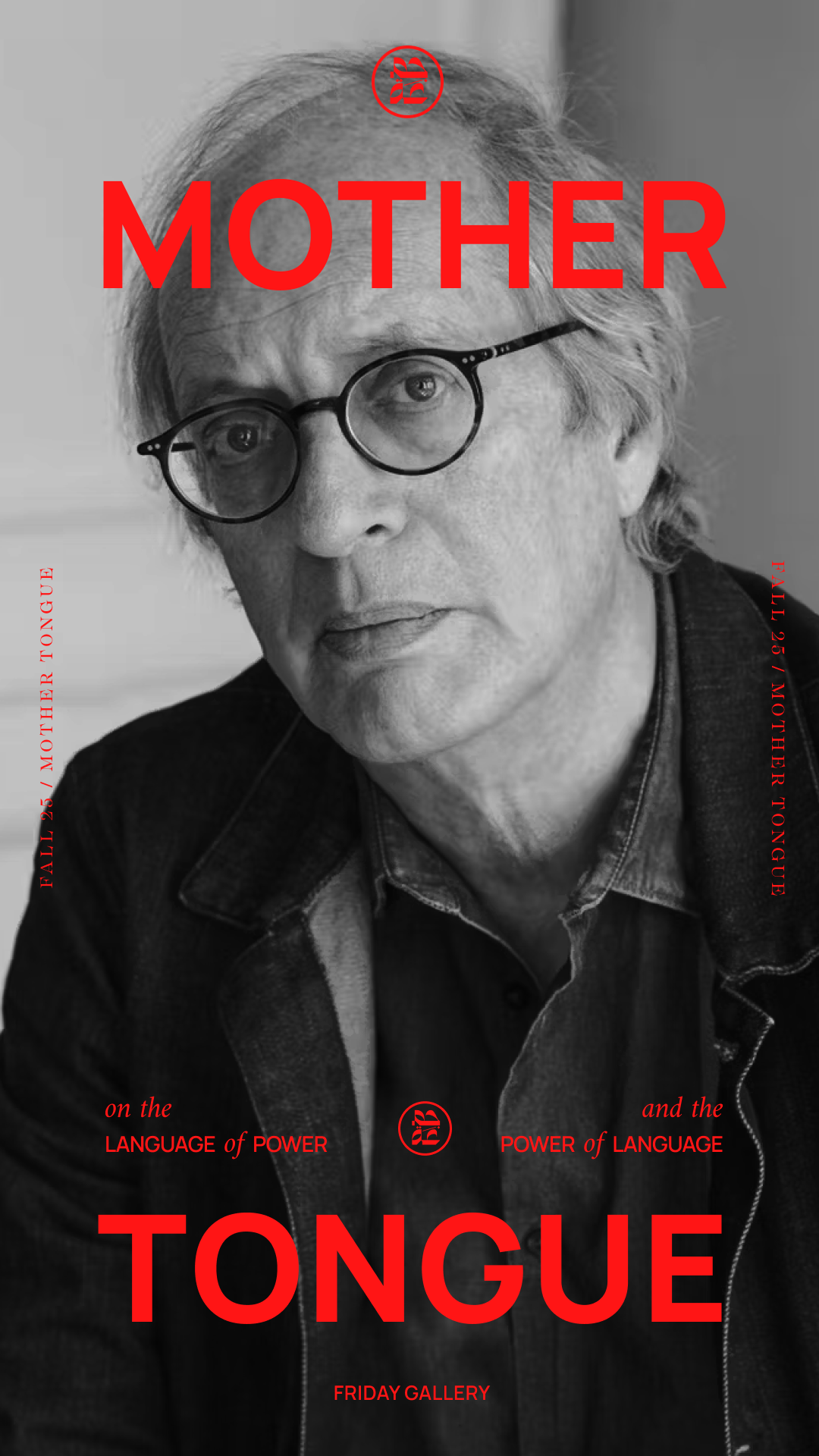

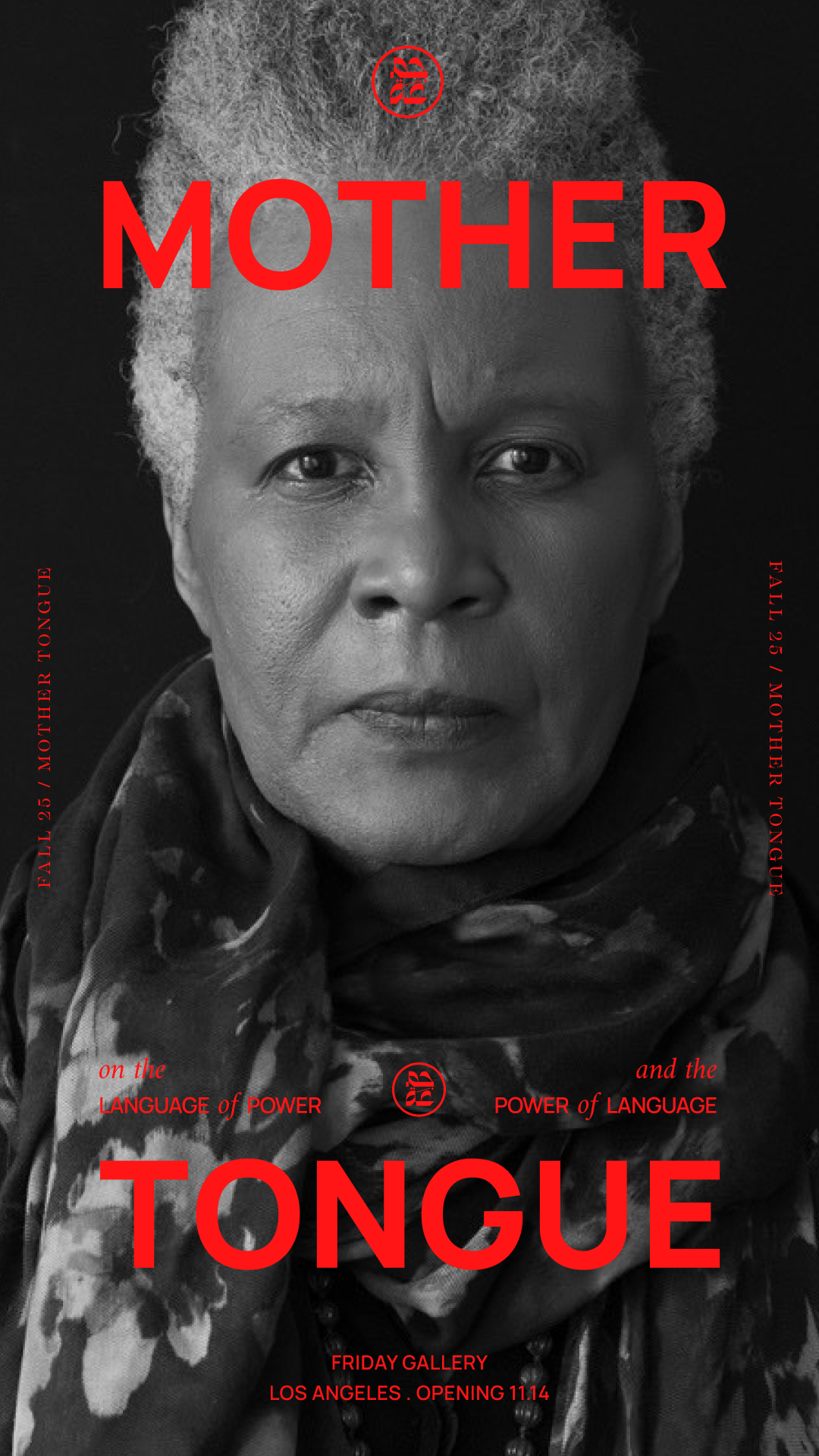

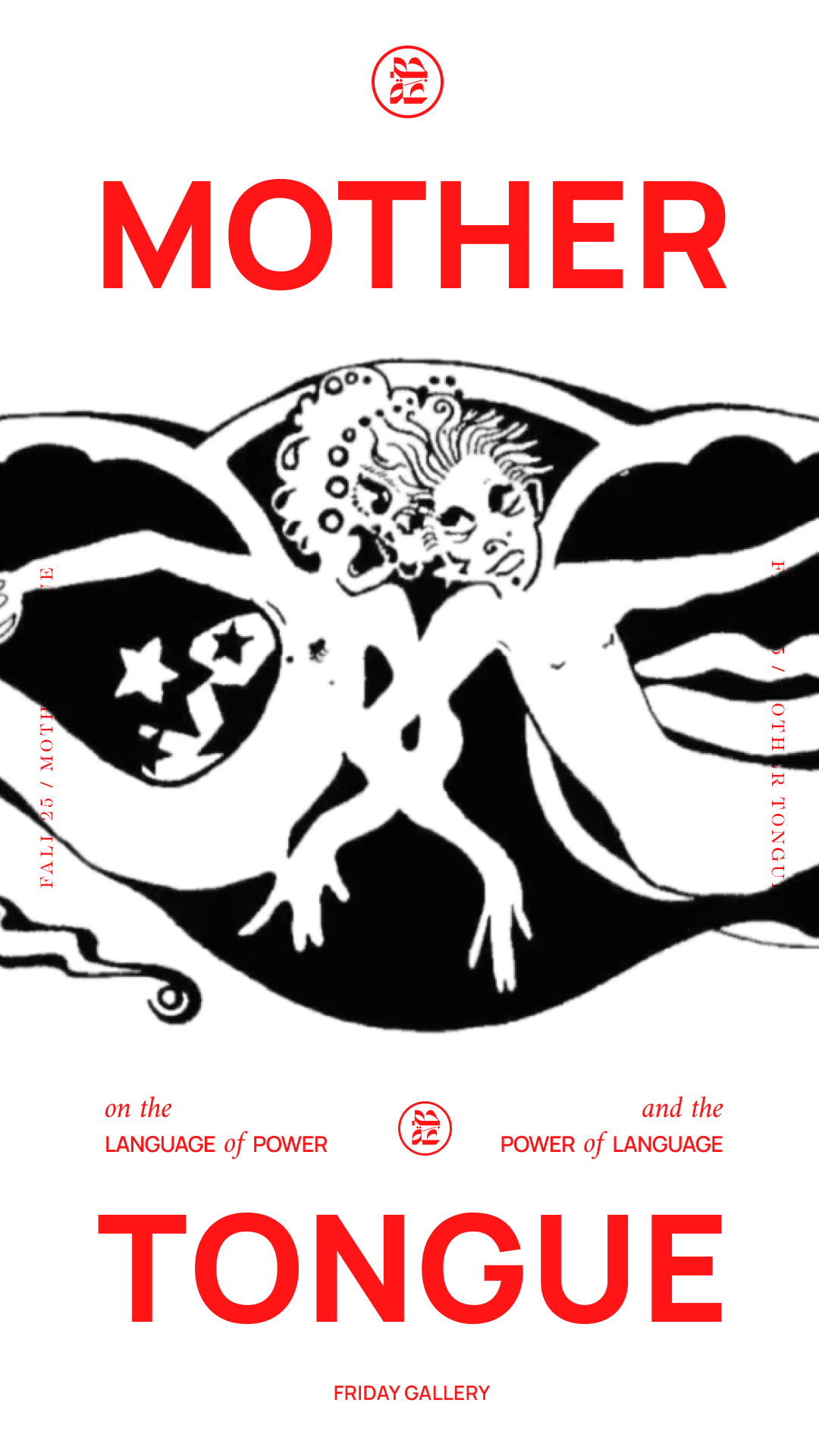

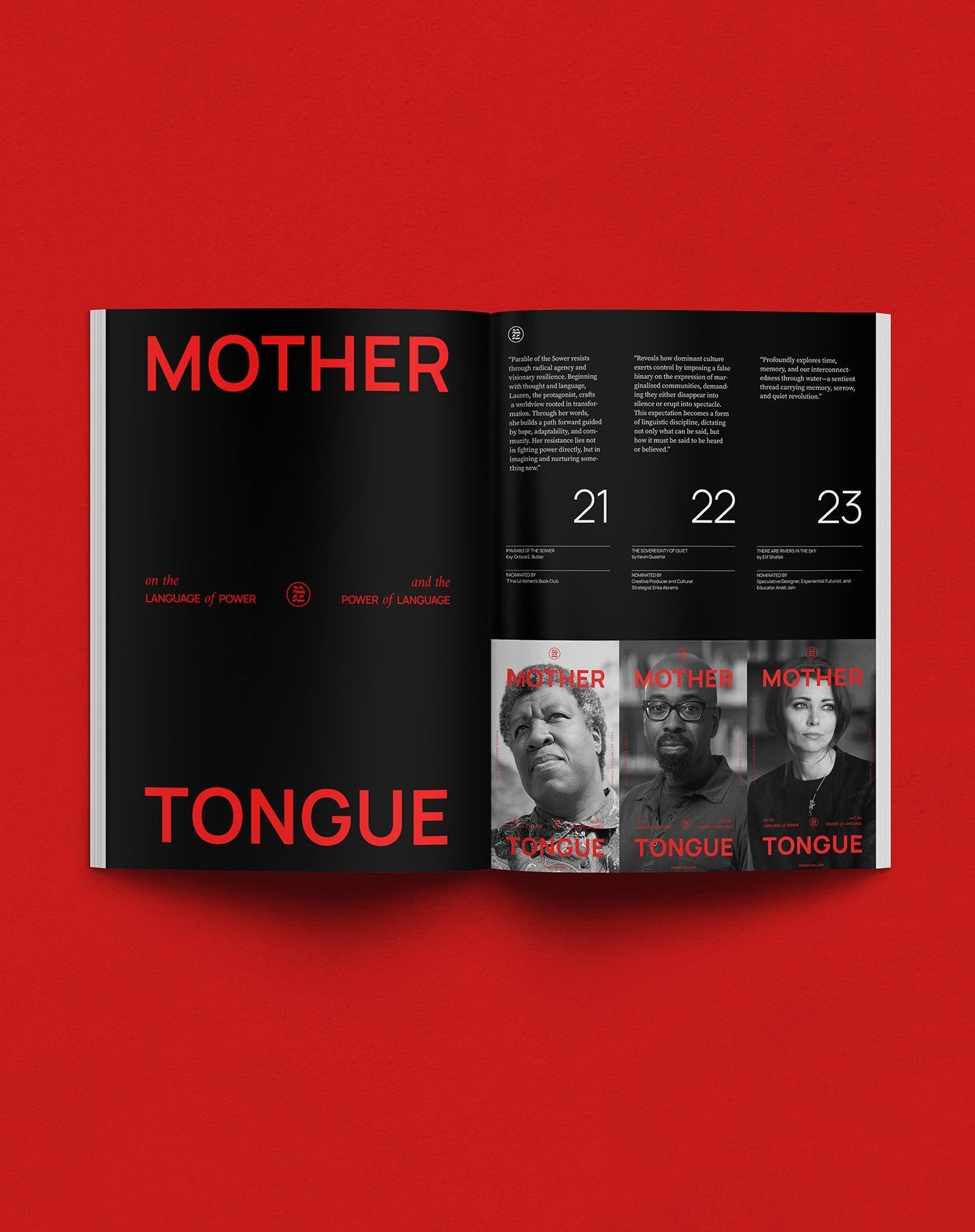

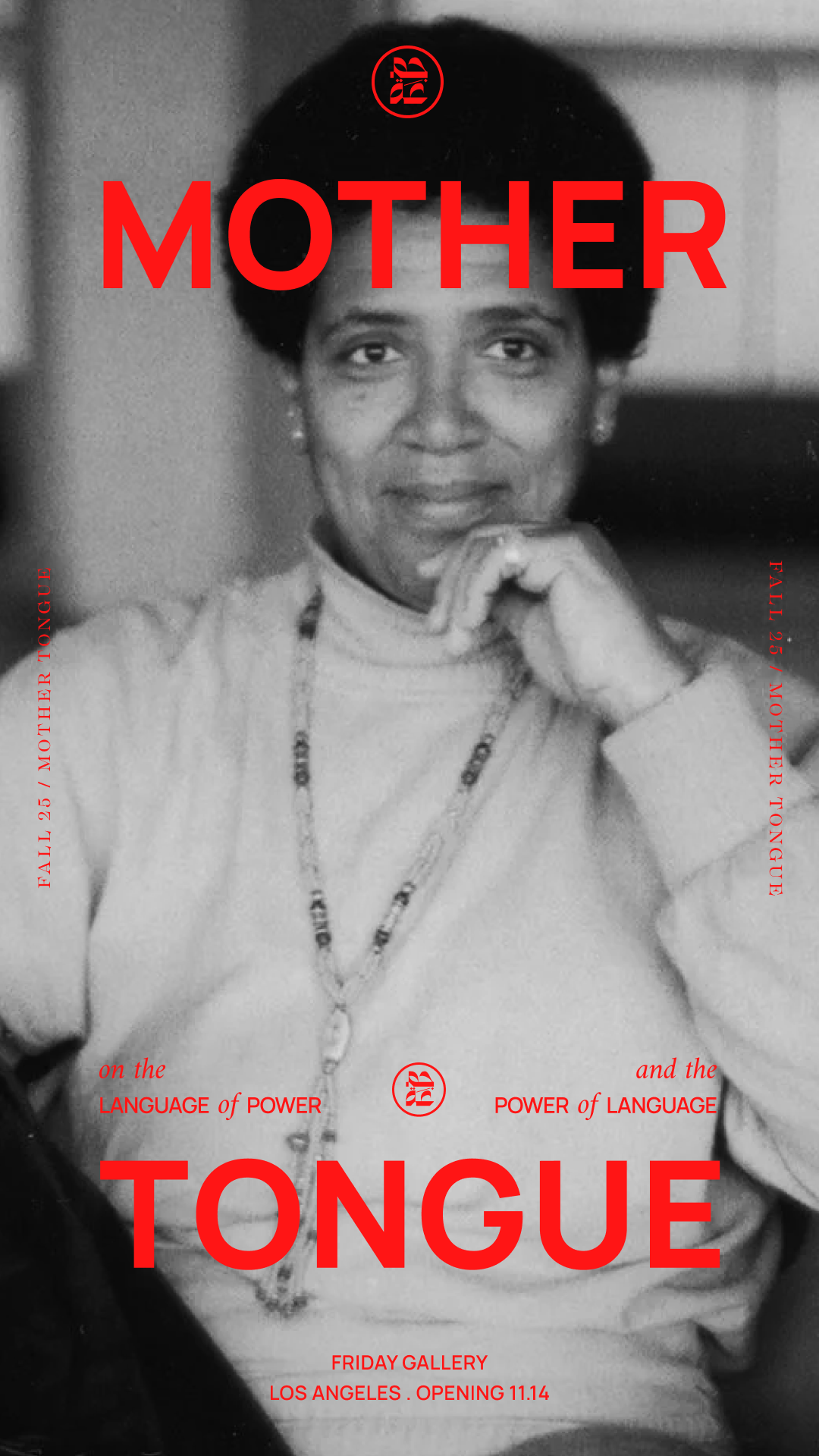

Mother Tongue

COLLECTION 1

Libration & Defiance

Dismantling the master tongue. Language that tears down the architectures of control, removes and renews distortion to bend reality to the reality we need. Language that creates new words for new worlds.

COLLECTION 2

Spells & Invocation

Language as spellcasting, mythmaking, and worldweaving. Holding memory of magical pasts, formenting both rebellion and care, and supporting the sacred revolutionary voice, where spirituality and power share a common tongue.

COLLECTION 3

Shape

shifting & Reclaiming

Language as protection. The voice as the instrument to speak back, to be heard, to break apart and re-unite. Rebirthing and recreating lost tongues and new tongues, resisting through hybridity, migration, and reinvention. The poetry of belonging, and the beauty of using language to define one’s own place in the universe.

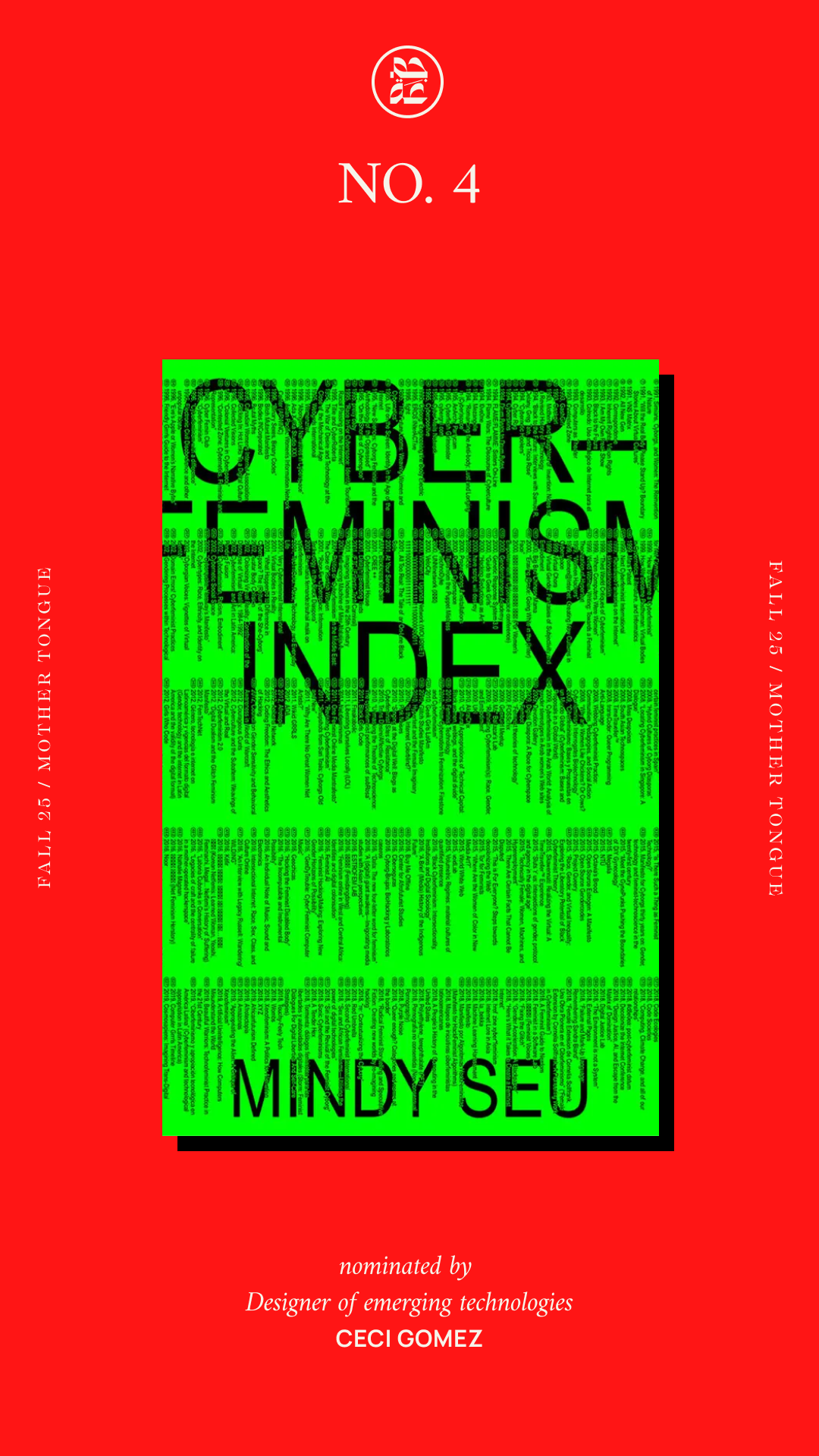

COLLECTION 4

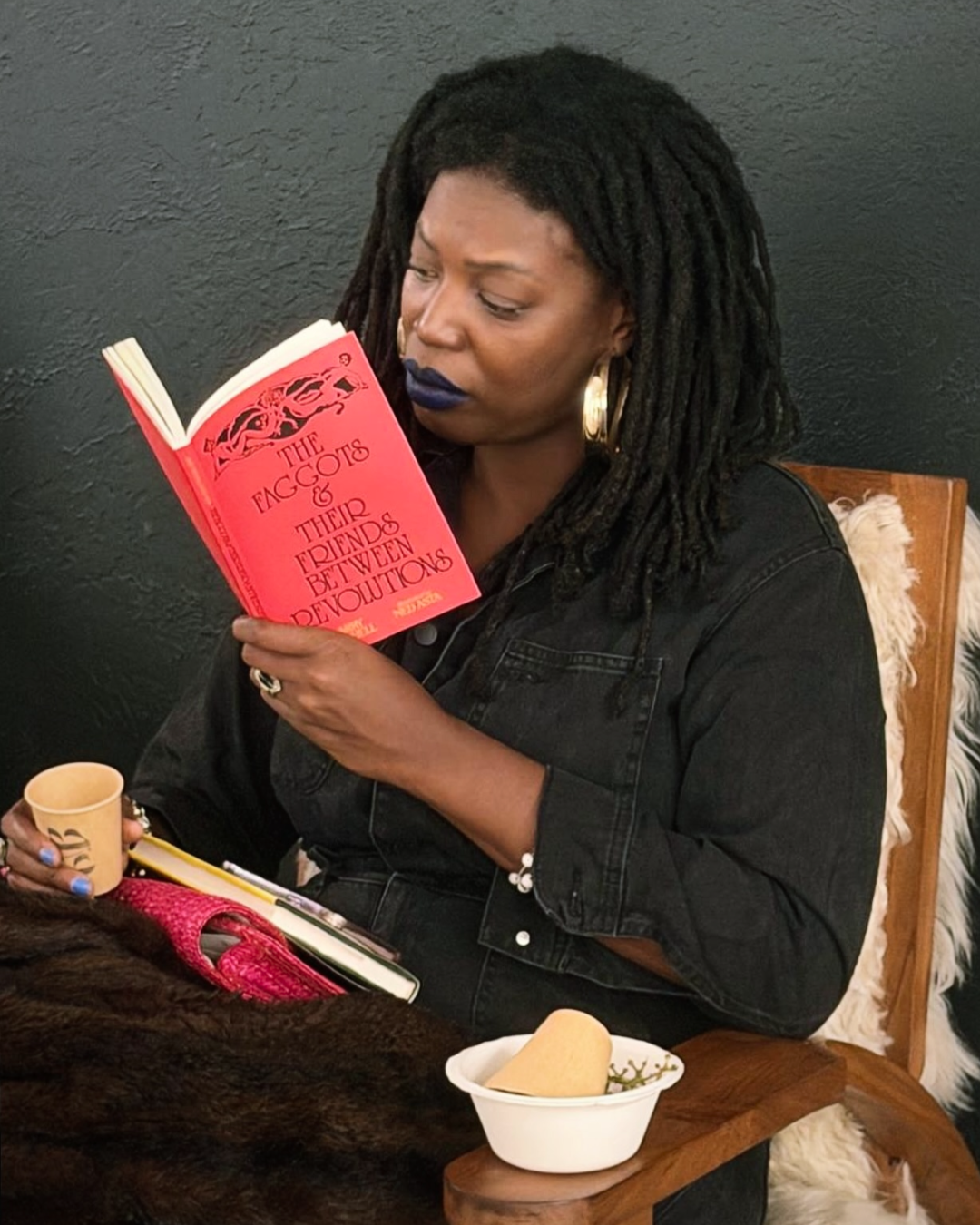

Subversion & Charm

Languages as charms, lures and invitations to hidden worlds, as codes and symbols and algorithms and frequencies. The symbolic and non-symbolic blended to deliver on the creative power that shapeshifts and tweaks and subverts. This is the home of the untranslateable, unparseable and the untamed.

COLLECTION 5

Rewilding & Enchantment

Speaking the ancient tongues of all beings, the more than human, the embodied creatures and the elemental. Stepping back to a time when humans remembered how to listen and speak with spirits and place and ancestors in all forms. Words that live in flower and flesh, muscle and murmurs.

Curator's Note

From Language Scholar Eva Barbarosa

To be invited to curate and complete a collection of one hundred books on mother tongues and language and power is a wonderous request. There are so many wonderful books that fit the bill. To settle on only one hundred books is the impossible task. There are simply too many, the field is too rich—across time and in so many languages, there are so many books that are so important.

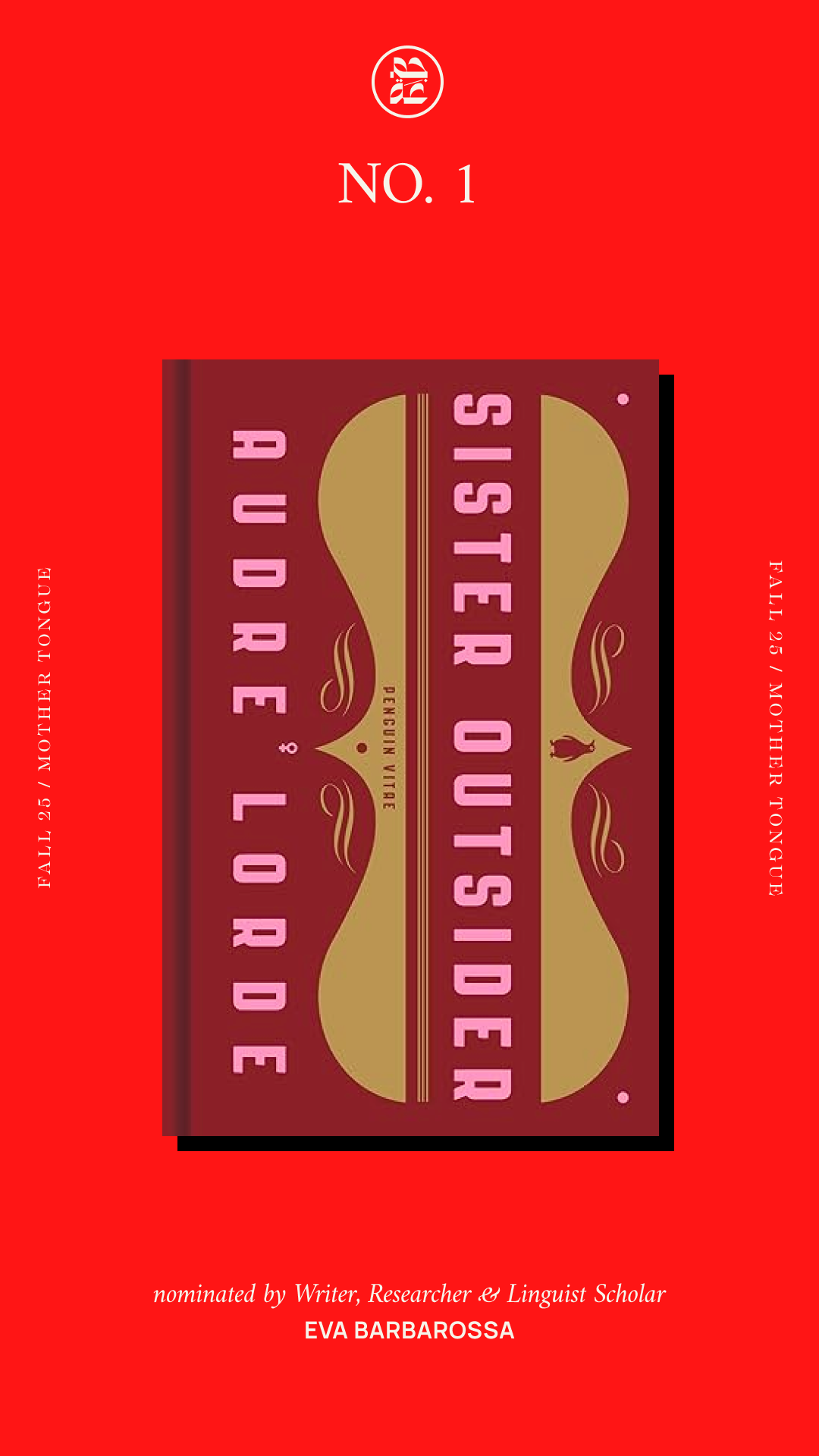

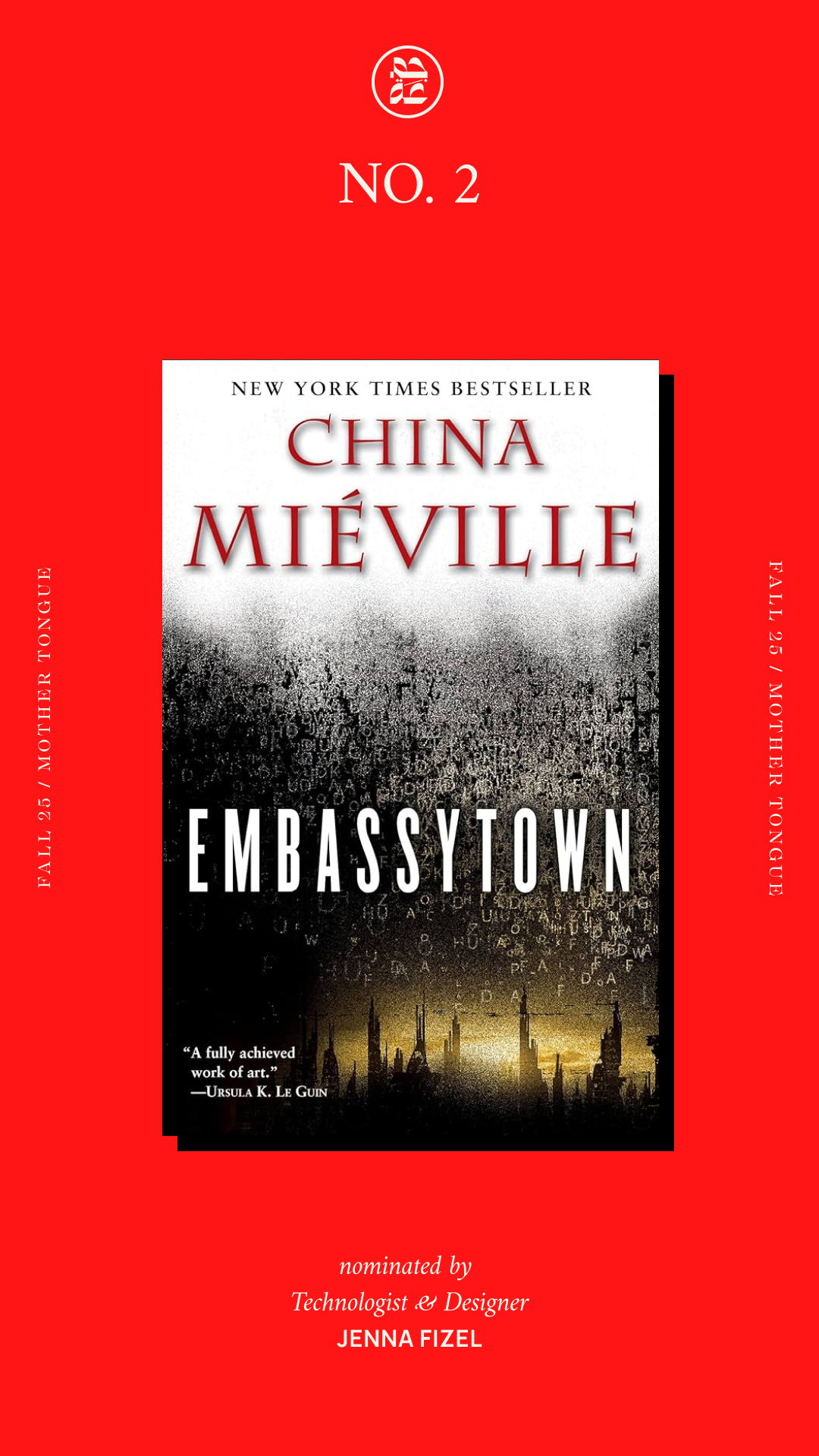

This collection began with seventy-four titles submitted by an eclectic band of cultural thinkers who submitted not only author and title, but very beautiful and very personal reasons as to why this was on the one book of all the possible books that they felt must be in this collection.

To these I have added twenty-six. Some are certainly ‘missing’, this is not a canon or a list of classics, to winnow to a hundred does bring a sense of loss for the many who did not fit on these shelves. I have taken the widely spread seventy-four books and added to them. I have stuffed in some cracks, stretched some threads, and, I admit, added a few of my favourites. Some of the books I have chosen to speak directly to those chosen by others, some to bend language itself.

Of the books in my house, a great many of them are about language, and yet another enormous part of the collection is both about the way language can be used, in poetry or satire or ancient myths or oral poems. There are words not only from the mouths of humans, but also plants and animals and dragons and elves across time, when all beings spoke and their stories were important, from the first to the last.

"Language is never neutral. It reveals and conceals, restructures, rewilds, enchants, and shapeshifts."

It is power, it gives us power, it reminds us of who we are, with defiance. It can liberate, but also it can do the opposite of these, it can oppress and erase and diminish and bind.

"These books are chosen to be free, to rebel, to hold our mother tongues and our languages of power close. To remind us of what can be, of how we can be, and of we can weave or break or reclaim."

These books are in relationships with each other, with the world. They are bound in patterns and shapes. One book may nest within another or lead to another. Some should be read together. Some should make us dreams of new ways to use language. Some are tied, and these ties can be ideas, language, people, place, themes or the way the language itself moves on the page and in the mouth and in the air.

My ideal outcome of breadth of form and place and language and meaning in these one hundred books is that each person who comes upon this library meets one or two or three new authors, or sees new connections, or finds ideas or inspiration or interest of some form. Finds something to strengthen or embolden or praise or share.

I would like to thank Mitch and Mubarak as well as the contributors for their books and personal reasons why this one book. And I would like to thank Lina Srivastava for her assistance in seeking to leave no agonizing gaps, though at the end the responsibility is mine.

May you all find beauty and inspiration in this library.

-Eva Barbarossa

.

EVA BARBAROSSA

I am a writer, scholar, linguist, researcher, and strategist. I currently split my time between researching and writing the cultural histories of invisible forces, writing about machines and AI from the POV of a linguistic anthropologist, and finishing writing up my PhD. When not being academic and artistic, I also can be found running research & strategy projects for clients (NIH, McCain Institute, and more) who are interesting in understanding how language, meaning, and culture impact their domains (genomics, human rights, precision medicine), what are the impacts and possibilities of AI on humans, and what these means for their goals and their intentions.

My love of languages, culture, and the stories we tell ourselves began long ago. An obsessive reader as a child (and now), I also became a learner of languages, in a desire to read in the original, and trace the threads of culture across time and place. I read from the ancients to the present, though I admit to being far less fluent in popular culture, unless it flings itself at me.

My book for Bloomsbury Academic’s Object Lessons series, magnet, launched to the world September 19, 2019. It is a survey of many of the ways humans have tried to understand what the magnet is, how magnetic fields work, and a comparison to the sophisticated usage of non-human species as well as, possibly, our far back ancestors.

For many years I worked on The Adelphi Project, a multi-year project to read 700 books published by Adelphi Edizioni in their Biblioteca catalogue. It has been a beautiful process of rediscovery, reconsideration, and reevaluation, far beyond the initial intent, which, retrospectively, was more akin to computational metaphysics. It also introduced me to Roberto Calasso, whose friendship added a richness to my life.

I try to write regularly on what I read about linguistics, language, culture, translation, and artificial intelligence, though it hasn’t been the best year for that. I am fascinated, as a central point, by the possible evolution of language by non-human intelligences, if we can call the machines intelligent, yet, and by the way the existence of machines (bots, robots, AIs, intelligent agents, sexbots) changes the way humans use language amongst themselves, and between themselves and the machines. The language/culture connection seems to be the least discussed in the discussions on AI, and on the ethics of AI, and one of these days I shall raise my voice louder, with so many interesting points that go beyond what the computational linguists (or the newly hatched computational behaviorists) seem to be considering or studying. Now that AI has exploded into the mainstream, it is all the more chaotic, and in many ways, seems far less thoughtful.

I’ve been a strategist, researcher and (former) designer of complex products, interactions, and experiences, starting first in story at National Geographic, and moving to health care, where I worked on experiences and ways of supporting sick children. Shared language/shared meaning and culture as the basis of making change became the sole focus of my work several years ago, and now I focus on linguistic and anthro methods to explore language to create frameworks and model for meaning, meaning shift, behavior and behavioral shift. I use this research to create complex system models to show how language and beliefs impact a space, and recommend products, services, communications, and languages that can support organizational needs. I only work on projects that I feel have a positive social impact. I am not looking to create coercive or obfuscated language that makes the world a less good place. There is plenty of that going around.

So how did it come to all of this? I have three degrees, and much of my study was in linguistics, anthropology, philology, culture, and geography. I fell in love with these things as a child, and they’ve stuck evermore. I also really wanted to be a pirate, when I was a child, then a Jesuit (I thought they sat around and read and studied all day, a little gardening, and that was all), and a cat burglar (I practiced, I like climbing and heights, and stealth.)

In the depths of Covid lockdown, I decided to pursue a PhD, which shall be done in early 2026. My research is on how we use language and song to have relationships with spirits of place, unseen beings, and in both ordinary and non-ordinary reality. I was fortunate to have done a significant part of my research in northern Mongolia, with the Darkhad’s, an experience that has forever changed my life.

I have a facility with languages (family trait), and can read many quite well, pick them up easily, and enjoy learning new ones. (Kio Stark wrote about me and my language learning ways, in her book Don’t Go Back to School: A Handbook for Learning Anything.) I’ve studied nine of them, formally, the rest, they just appear. I tend to say I read languages, as I care less about speaking them. I want to read and hear in the original language, and while I love translation and am fascinated with how it works, I still would prefer to know them all. That’s just the way I am. I have no desire to live forever, but a few hundreds years, so I could fluently read every written text in the original, well, count me in.

I have spent — and continue to spend — a lot of time traveling. I like remote places and travel by slow forms; I like to talk to strangers because they tell me extraordinary stories about who they are, and why, and the ways in which they make themselves a reality. I’ve traveled more than 30k miles by ferry in the past five years. Some of those stories are here. I’ve been to almost as many countries as I am years old, and now that I write that, I should fix that. More countries than years, sounds like a fantastic goal.

For images of my travels, @ekbarbarossa, for images of The Adelphi Project, @theadelphiproject, for my obsession with AI, language, translation, and the evolution of languages in machines, I write at akathesia.com.