MOTHER TONGUE

ON VIEW NOV 14 — FEB 6

with works by

Behnaz Farahi

Caroline Monnet

Cryptik

Raymundo T. Reynoso

Salomón Huerta

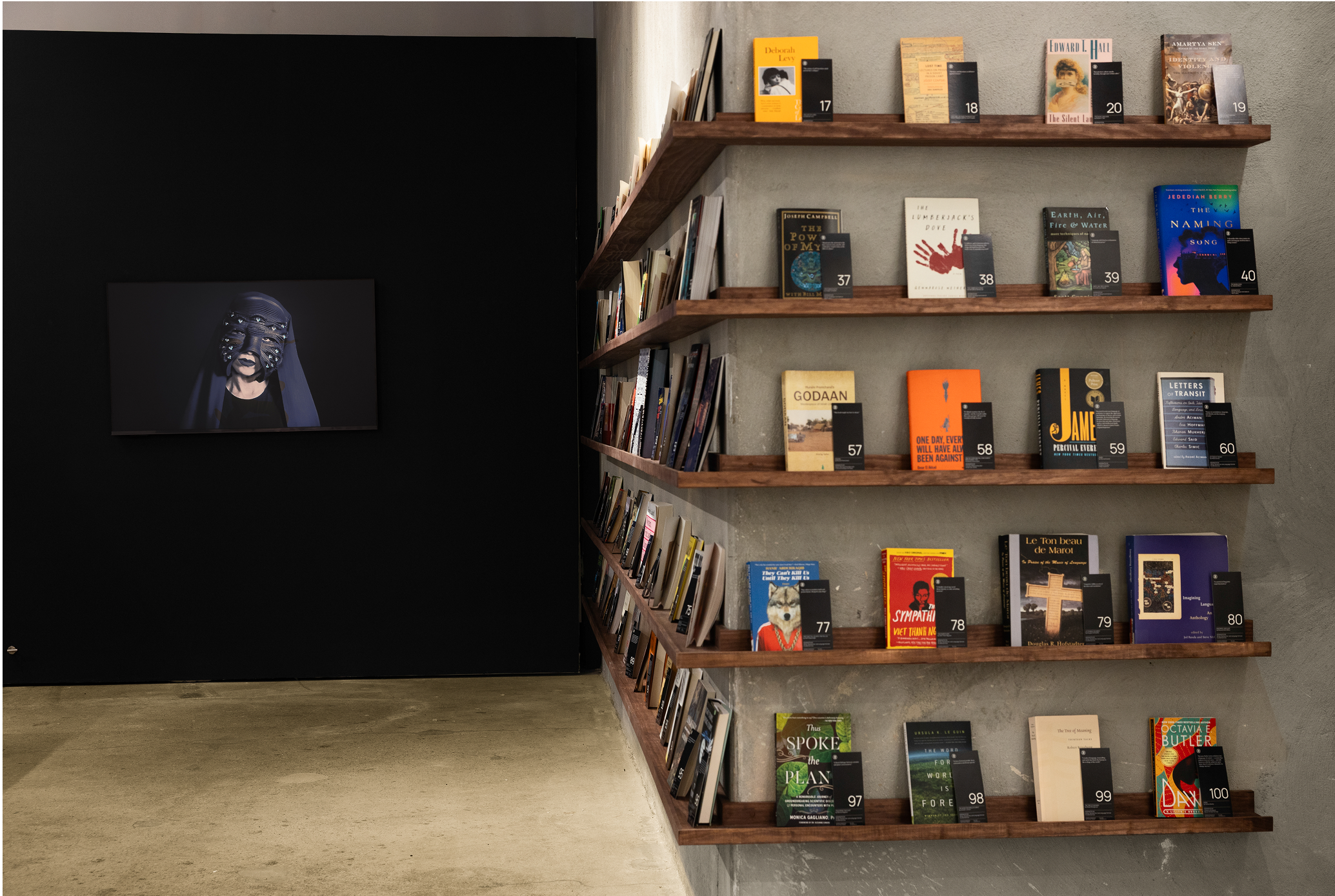

Mother Tongue asks: “What does it mean to speak the language of power?” In this moment, more than ever, words matter. Words seduce. Words distort. Words unite. Words intoxicate. Power knows this well, with language as its chosen lover. Our fall season brings together artists exploring the contours of language and power, from word to symbol, from myth to hidden messages.

ALL WORKS

Mother Tongue Artists

FIVE QUESTIONS WITH

ARTIST PROFILE

FIVE QUESTIONS WITH

FIVE QUESTIONS WITH

Caroline Monnet

Nigàsimonìgin

Nigàsimonìgin — meaning “canvas” in Anishinaabemowin — transforms a hidden building material into a membrane of memory. Through this work, I make visible what is often unseen: Indigenous language, knowledge, and resilience. It is an act of presence, a declaration that our perspectives are alive, valid, and enduring. By printing on an air filter, the part of a building that breathes, the protective layer, I reveal the quiet strength that sustains our communities. It is a reminder that we belong to the land, we can not own and claim it. We carry it in every breath.

The patterns pay tribute to the ancestral tradition of “birch bark biting,” using teeth to create shapes in thin, folded layers of birch bark. When unfolded, they reveal perfectly symmetrical geometric patterns. The symbols are a communication form connected to different family lineages, carrying home along with them.

CAROLINE MONNET

Caroline Monnet is a multidisciplinary artist of Anishinaabe and French ancestry, originally from the Outaouais region, who lives and works in Mooniyang/Montreal. With a deep interest in communicating Indigenous identity through complex cultural narratives, her artistic and cinematographic work grapples with colonialism’s impact, updating outdated systems with anishinaabeg methodologies.

With bachelor's degrees in sociology and communications from the University of Ottawa and the University of Granada (Spain), her work has been shown in solo exhibitions, notably at the Montreal Museum of Fine Arts (Canada), Kunsthalle Schirn (Frankfurt, Germany), Arsenal art contemporain (New York, USA), Centre International d'Art et du paysage de l'île de Vassivière (France) and the University of Toronto Art Museum (Canada). The artist has also exhibited at the Whitney Biennial (New York, USA), the Toronto Art Biennial (Canada), KØS Museum (Køge, Denmark), Musée d'art contemporain (Montréal, Canada) and the National Gallery of Canada (Ottawa, Canada), among others.

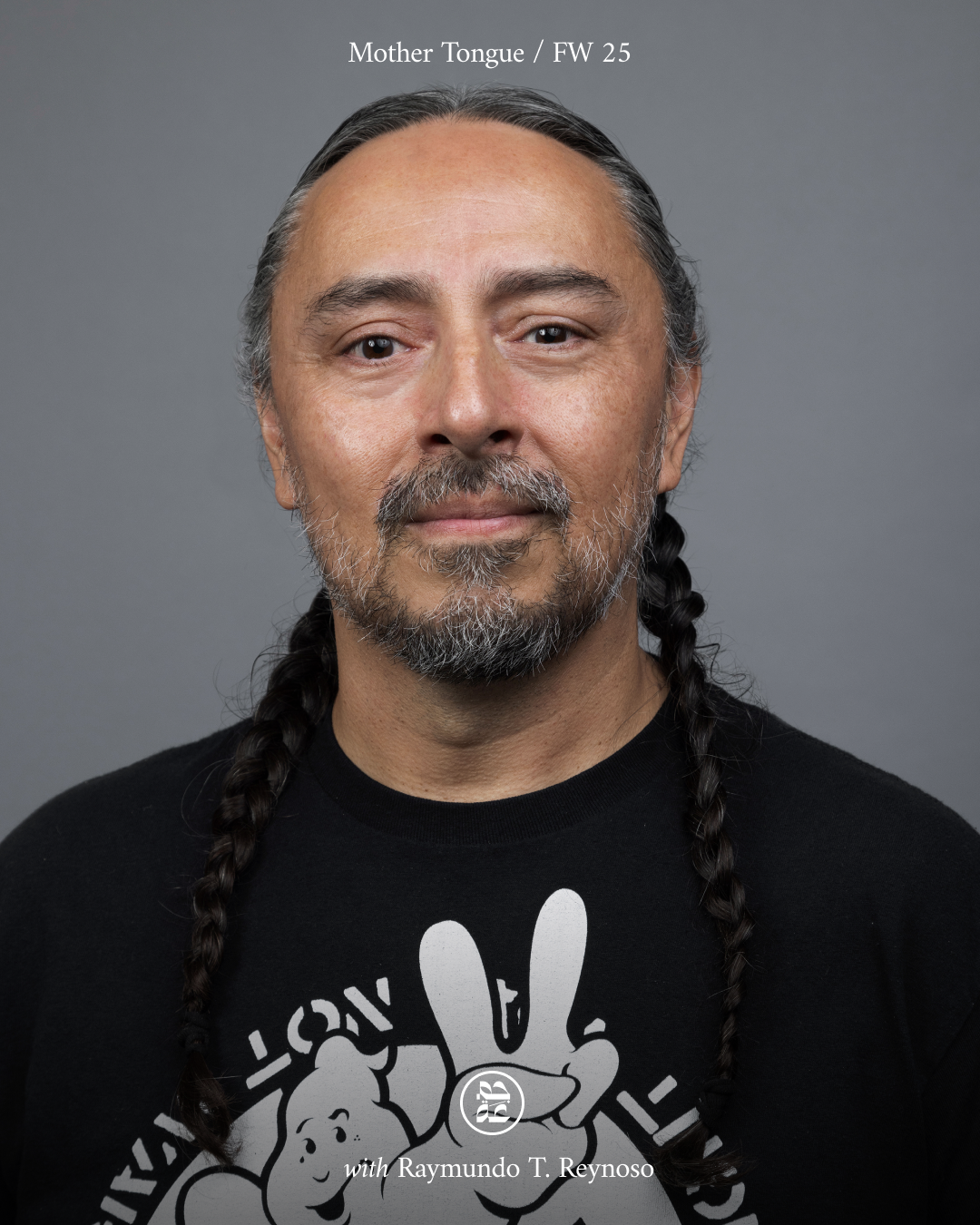

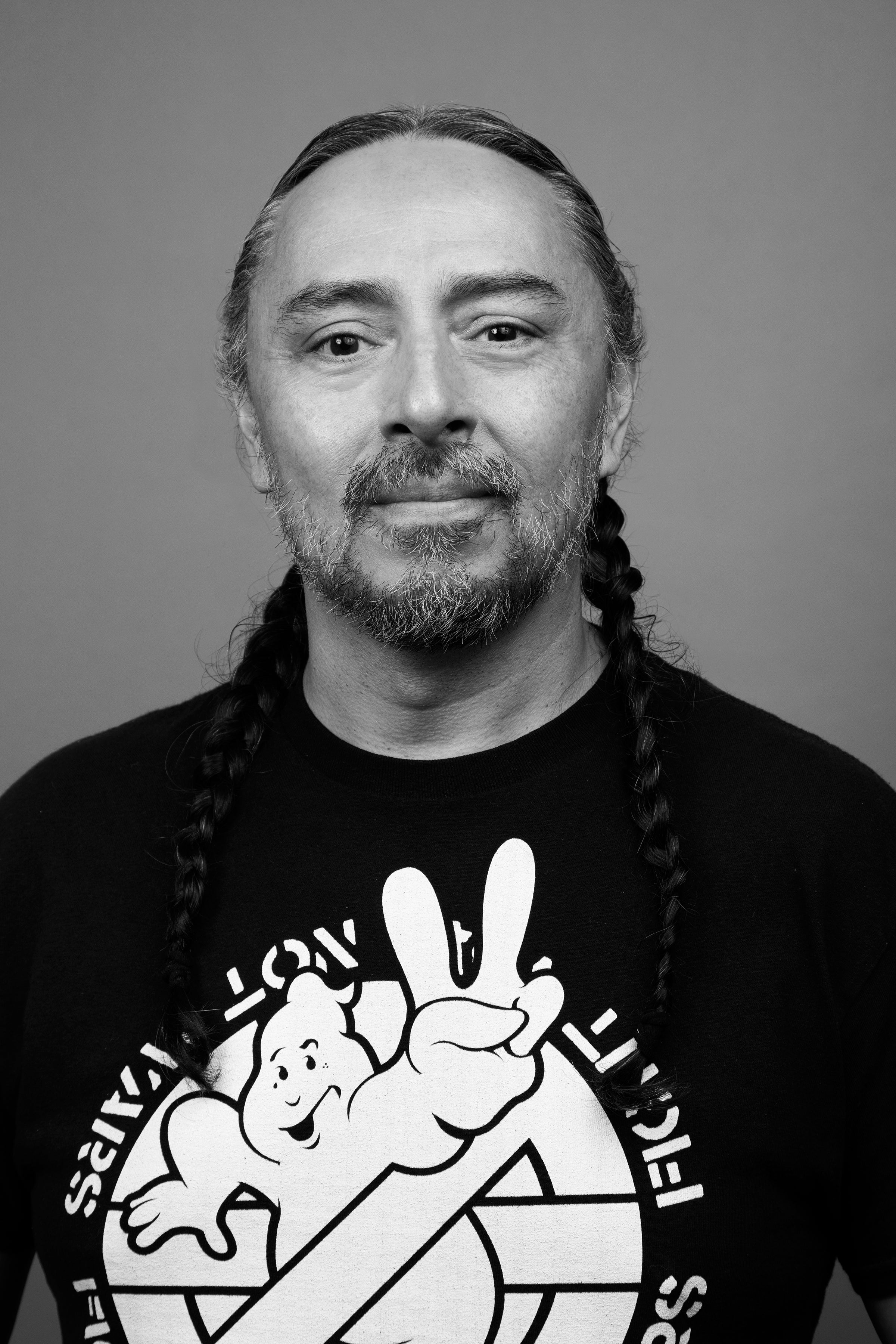

Raymundo T. Reynoso

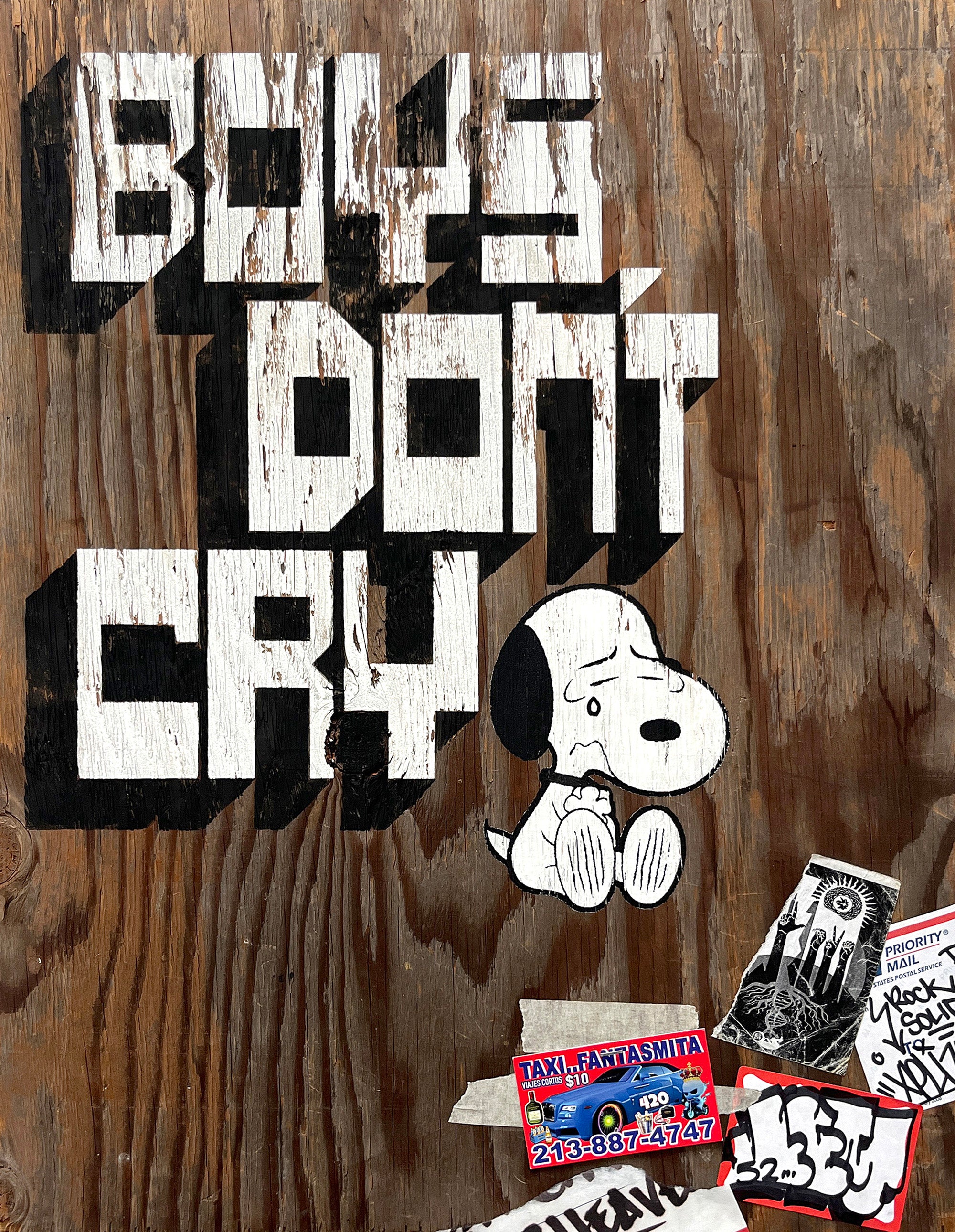

Ponte las Pilas

"My Ponte las Pilas installation is at its core an exploration of language and its power, both in my mother tongue (Spanish) and my adopted language (English.) Literally meaning (roughly) “Put in your batteries.” It is an oft-repeated phrase in Spanish intended to offer a quick encouraging course of action to address an issue being faced. It is a phrase that in English is not quite “pull yourself up by the bootstraps,” “keep your chin up,” “try hard(er),” or in the parlance of marketing and advertising, “just do it,” but nevertheless, it intends something similar.

The installation is comprised of multiple elements. It combines works from my Imaginary Found Objects series (an ongoing project that incorporates musings on imagined signage based on words, phrases, and typography inspired by vernacular graphics from my city of birth (CDMX) and the city I call home (Los Angeles); works from my Means of Production series, centering instances of the existence and resilience of working class folx in marginalized and working class communities, primarily in L.A. and incorporating the commonalities that tie us with other people across the global south and the world at large." - Raymundo T. Reynoso

RAYMUNDO T. REYNOSO

"I was born in Mexico City and moved to Los Angeles when I was six years old. Drawing from my lived experiences as a BIPOC immigrant, my work focuses thematically on intersectional issues such as labor injustice, wealth inequality, lack of affordable housing, discrimination, and mental health.

My art is interdisciplinary and incorporates painting, printmaking, digital imaging, photography, lettering, and collage. I aim to center the unseen people of Los Angeles, echoing Dr. Cornel West's interpretation of Sly & the Family Stone's seminal song "Everyday People,” by amplifying narratives that lift up the contributions of communities of color and the importance of labor and the working class in building a more equitable society.

I adhere to the words of Doña Fili, Water Defender in Mexico City. In the film about revolutionary artist and musician León Chávez Teixeiro “Mujer. Se Va La Vida, Compañera," Doña Fili emphasizes that art plays a vital role in advocating for human rights in marginalized communities and says: "Art speaks to the People and lets us know we are seen."

Desde abajo y a la izquierda.

Behnaz Farahi

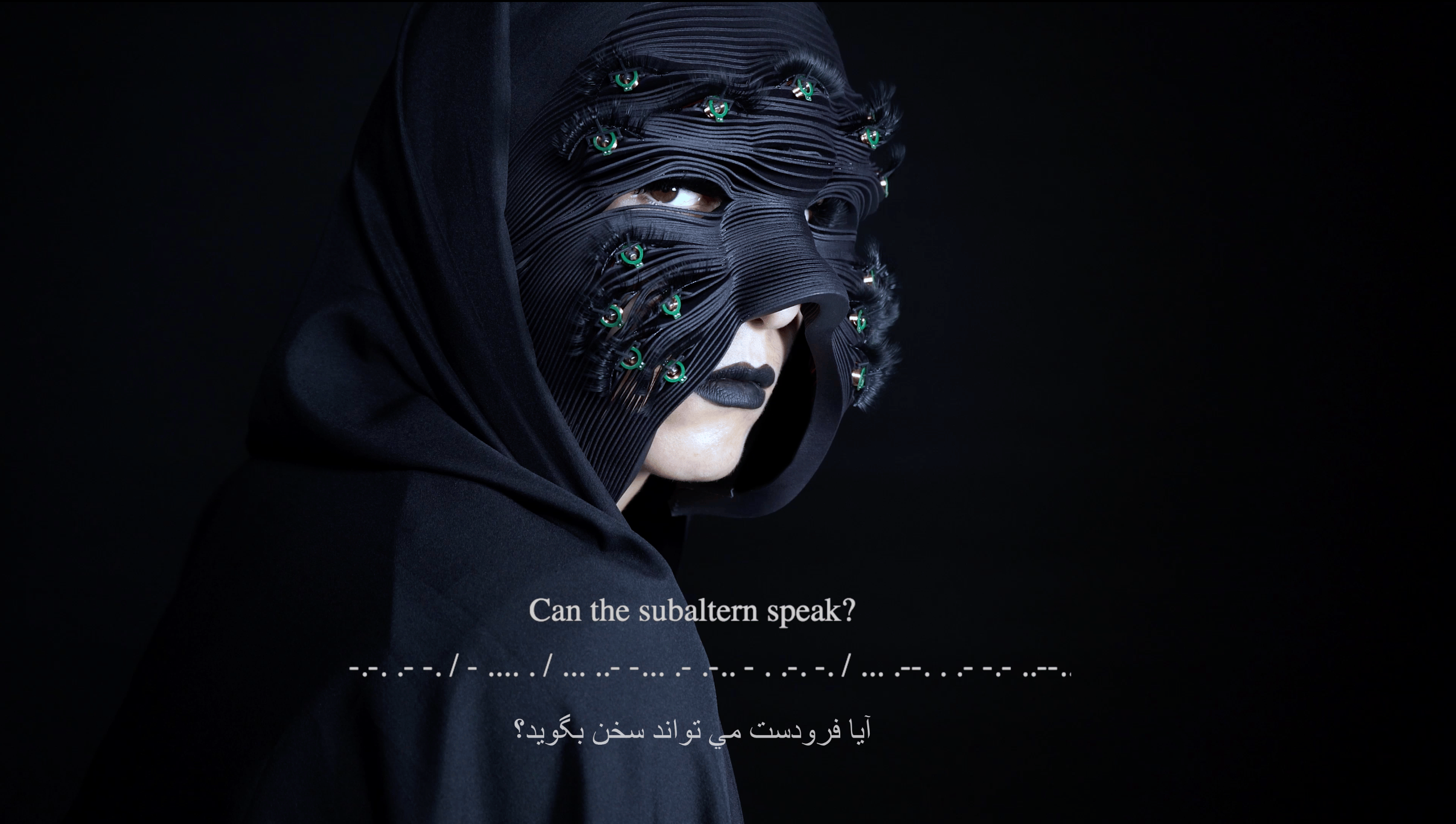

Can the Subaltern Speak?

In her seminal article “Can The Subaltern Speak?” feminist theorist, Gayatri Spivak, asks whether it might be possible for the colonized – the subaltern – to have a voice in the face of colonial oppression. How might we reframe this same question in the context of contemporary digital culture? How could we find a way for the subaltern to speak that would also undermine the power of the oppressor?

This project is inspired by the intriguing historical masks worn by the Bandari women from southern Iran. Legend has it that these masks were developed during Portuguese colonial rule, as a way of protecting the wearer from the gaze of slave masters looking for pretty women. Viewed from a contemporary perspective, these masks can be seen as a means of oppressing women under patriarchal colonial rule. In this project two masks begin to develop their own language to communicate with each other, blinking their eyelashes in rapid succession, using AI generated Morse code.

Behnaz Farahi

Behnaz Farahi is a designer, creative technologist and critical maker. Currently, she is an Assistant Professor at the MIT Media Lab, where she leads the Critical Matter Research Group. Trained as an architect, she explores how to foster an empathetic relationship between the human body and the space around it through the implementation of emerging technologies.

Her goal is to enhance the interaction between human beings and the built environment by following morphological, and behavioral principles inspired by natural systems. Her work addresses critical issues such as feminism, emotion, bodily perception and social interaction. She specializes in computational design, interactive technologies, additive manufacturing and digital fabrication technologies.

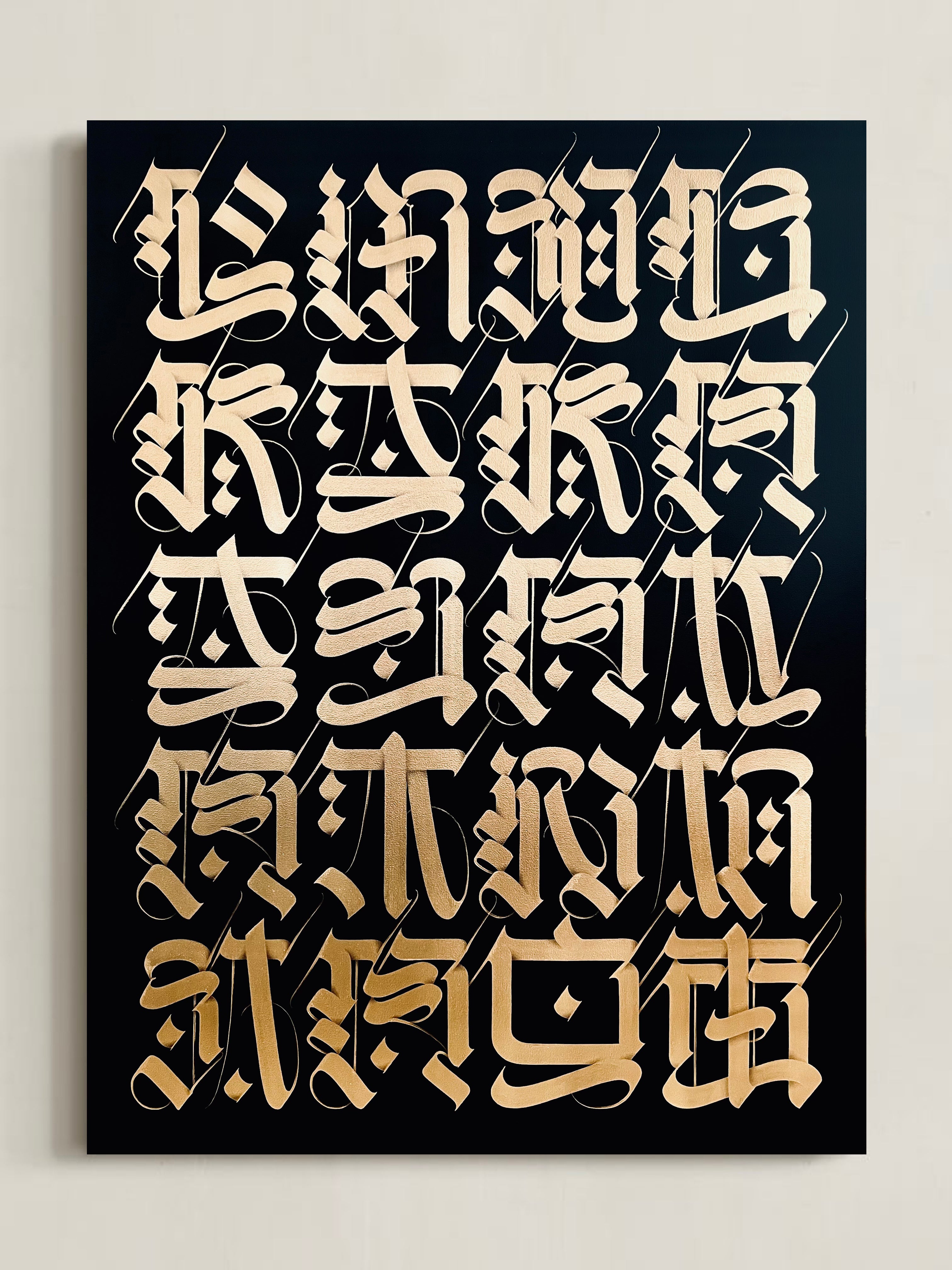

Cryptik

The Brilliant Light

"In these times of great change and global uncertainty, there is one prayer that always comes to mind, "Lokah Samastah Sukhino Bhavantu," which translates to, "May all beings everywhere be happy and free, and may the thoughts, words and actions of my own life contribute in some way to that happiness and to that freedom for all."

This ancient Sanskrit prayer moves us from our personal, egoic self, towards embracing greater peace and compassion for all life. It is a blessing for global well-being and collective peace in our world, reminding us of the interconnectedness we all share. Through this prayer may we become more mindful of the way our thoughts, words and actions affect others, as well as, our planet." - Cryptik

Cryptik

CRYPTIK is a Los Angeles-based artist whose evocative, meticulously crafted artwork explores themes of spirituality, consciousness, and our connection to the Divine. Known for his distinctive calligraphy, CRYPTIK has carved a unique niche in the art world with his stylized letterforms - a reinterpretation of the Latin alphabet that serves as the cornerstone of his expression. His pieces interweave spiritual and philosophical teachings, inviting viewers on a journey of introspection and revelation.

Inspired by some of the world’s oldest writing systems and reimagined through a contemporary lens, CRYPTIK’s calligraphy evokes a time when the written word was considered sacred, transcending both cultural and temporal confines. Guided by an enduring belief in the power of words, his meditative process shapes each piece. Every stroke captures the essence of diverse philosophies, imbuing it with a sense of wonder and meaning.

Beyond galleries, CRYPTIK brings his art into public spaces through large-scale murals and installations worldwide, transforming urban environments into sanctuaries of contemplation. These public works make his art accessible to diverse audiences, fostering a sense of community and connection. Blending creativity, spirituality, and social consciousness, his art speaks to the shared human experience. With themes that surpass societal and geographical limits, his work is a language of universality - a singular human script.

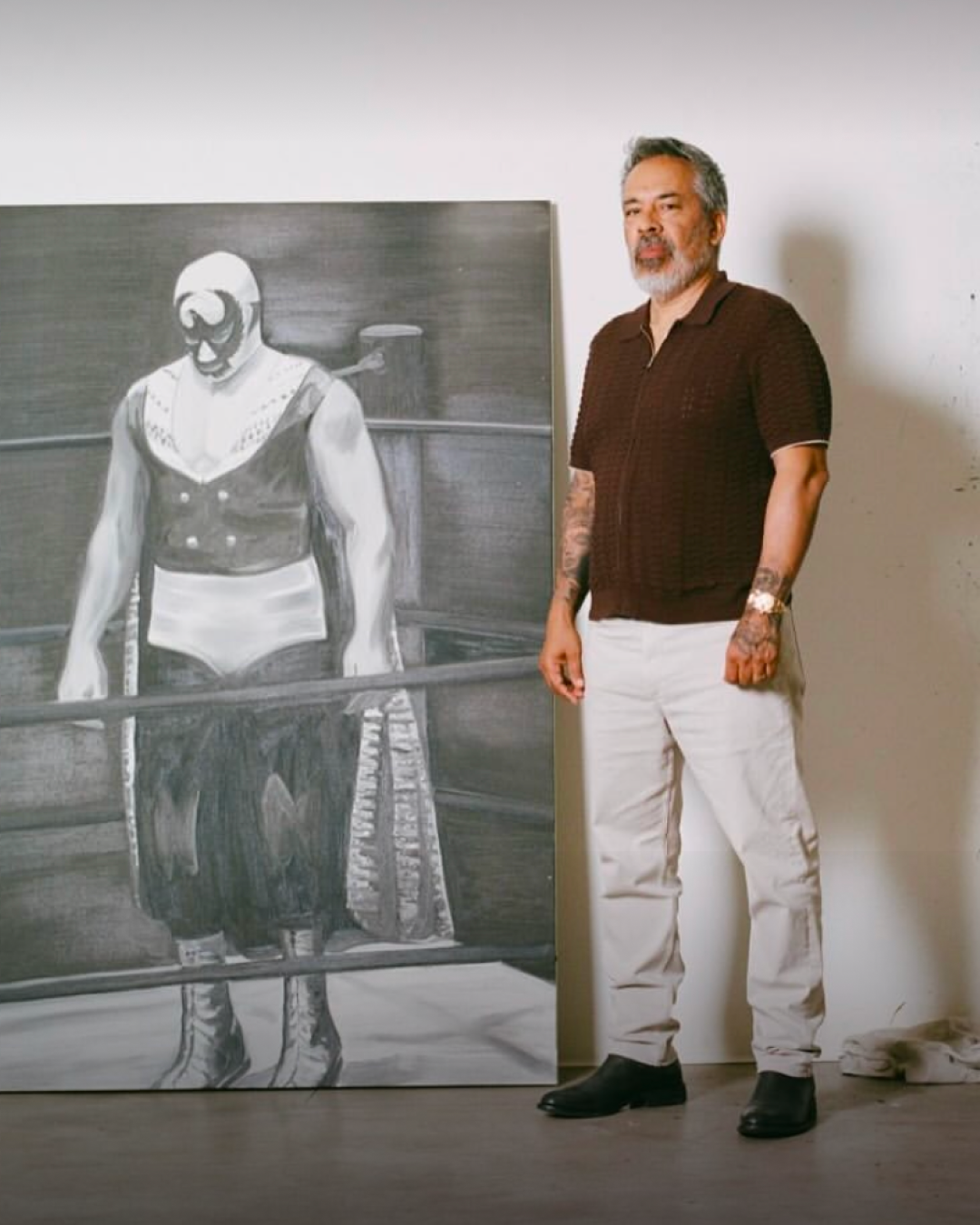

Salomón Huerta

When We Had Names

"This collection of minature oil portraits are of family members from Pajacuarán, Michoacán. The photos were taken by a photographer documenting the town, capturing them before many crossed into the United States.

In Mexico, they felt a sense of oneness and freedom as they moved through their homeland. Crossing the border through hostile terrain, arriving in a place where they weren’t welcomed and didn’t know the language, yet still finding a way to succeed. Now, however, they are often treated like animals under a racist government that believes we don’t belong on stolen land that was never theirs. These small paintings honor proud individuals returning home, deserving of the same respect and and dignity as any other human being." - Salomón Huerta

Salomón Huerta

My work, spanning over three decades, is rooted in exploring personal history, memory and the tension between presence and absence. The back of the heads, houses, and standing figures in my paintings are conceptual studies—formal exercises in repetition, scale and quiet observation.

At its core, my portraits are about observation. I have painted gang members, boxers, and luchadores (Mexican wrestlers)—figures from my upbringing—without glorification or judgment. I paint them simply as they are.

I continue to work in representational painting, primarily portraiture and landscapes but my approach remains fluid. Each body of work connects through shared themes: memory, tension and the way objects and figures hold power. In the end, I want my paintings to provoke reflection and dialogue. Who holds the real power—the individual or the structures that shape them?